By Sara K. Ahmed

With excerpts from Being the Change: Lessons and Strategies to Teach Social Comprehension, Heinemann Publishing, 2018

Ta-Nehisi Coates (author of Between the World and Me and Marvel’s new-era Black Panther books) took the stage in an auditorium full of revering educators at the National Council for Teachers of English in November of 2016. With palpable energy around the recent Presidential Election, he was asked how he felt about the outcome.

Coates was quick to say that he is not surprised. “Look, if you know the history of this country. If you understand the period of time during and after the Reconstruction (an era Coates describes in his 2014 essay, The Case for Reparations, where Terrorism carried the day) you’re not surprised at the outcome of this election.”

In synthesizing his words and my own knowledge of American history, Coates offered the audience a confronting truth: Our new Administration ran on a campaign of bigotry and oppression–and won.

That has stayed with me as a valuable lesson of 2016: To slow down my emotional response to any news and turn towards the importance of knowing our history, then facing it with full candor and shame to make sense of the present. So, rather than quickly posting to social media how I am shocked or appalled that this isn’t America, I turn to history.

As we round out the last month of 2018, I can’t help but reflect on where we are exactly two years after that conversation. The headline content that continues to cycle across my various medias looks something like this:

Migrant children still separated from their parents or put in camps.

Native Americans fighting to defend their lands.

Targeted mass shootings in schools and places of worship.

Swastikas tagged in the personal and public spaces of schools, offices, and places of worship.

Individuals being denied basic rights and visibility based on their gender identification.

Women’s bodies governed by legislation.

Women of Color break barriers and elected to Congress.

Shooting of another black American by a police officer.

European leaders at odds on the migrant crisis.

Tear-gassed families searching for the safety of asylum.

Public schools, unresourced and unsanitary for learning.

Marine animals victimized by human plastic consumption.

The Press being denied their right to report freely without fear of tyranny and harm.

Hurricanes and Wildfires.

Certainly not an exhaustive list but enough to burst with fury into threads on social media, tossed around in polarized echo chambers, and left for fodder until the next headline makes it way into cycle. The dispirited, social media-scrolling-me laments; Another news cycle. Another post claiming shock: “This isn’t America.” The spirited-me turns to history; inquires into patterns, constants, truths and opportunities for human connection in an ever-changing world of 24/7 media reporting.

Some truths that continue to rise to the top of my inquiry:

- Hate crimes and Nationalism are on the rise across America (and Canada and Europe).

- Bigotry and oppression continue to cycle from the highest office to the classroom next door, unchecked.

- History teaches us that this, with all of its progressive democratic beauty, discourse and idealism, is very much America.

In the chapter Finding Humanity in Ourselves and in Others, of my newest book, Being the Change, I turn to history to help us all make sense of how our everyday lives and actions implicate larger systems in society. In the beginning of the chapter, I list The Ten Stages of Genocide as defined by Gregory H. Stanton:

- Classification– dividing society into “us” and “them,” stripping citizenship of targeted groups.

- Symbolization-naming or imposing symbols on classification (Jews, Tutsi, stars)

- Discrimination– using legal or cultural power to exclude groups from full civil rights.

- Dehumanization– portraying targeted groups as subhuman (vermin, diseases, traitors, criminals, infidels, terrorists)

- Organization– organizing, training, and arming hate groups, armies, and militias

- Polarization-arresting moderate opponents as traitors, propaganda against “enemies of the people”

- Preparation-planning, identification of victims, training of arming killers

- Persecution– expropriation, forced displacement to ghettos, concentration camps

- Extermination-physical killing, torture, mass rape, social and cultural destruction

- Denial– minimizing statistics, blaming victims or war or famine, denying “intent”

Reprinted in Being the Change permission by the author Gregory H. Stanton, Founding Chairman of Genocide Watch.

If genocide feels like an extreme leap to you from what we see in the headlines, we can start with our daily lives-our most immediate history. Consider where you send your kids to school, the distance you travel to buy fresh groceries, the homes in your neighborhood, the people in your most trusted circles. Consider if you identify with the perpetrators, victims, bystanders, or upstanders of the above headlines.

The human condition is built around membership, belonging to a group. Thanks to our bias, we respond better to those who look like us. We covet sameness. For anyone outside of what we center as dominant norms, we may only have partial information due to lack of experience, interaction, and exposure. Here begins the slippery slope of action towards those we “other”: we classify entire groups (us and them), dehumanize (terrorists, criminals), polarize (“enemy of the people”). Anyone who has an understanding of the The Holocaust, Rwandan or Armenian genocide knows that these stages are not necessarily linear. That they all can operate throughout the process and that everyone’s identity is at stake and we all have a role. The dispositions that are foundational to atrocities are at work in our lives every single day.

Genocide is preceded by hate rhetoric, by complicity, by bystanders living in an “ignorance is bliss” state. I argue in Being the Change that ignorance is not bliss. Ignorance is a luxury of the privileged and a barrier to the unnoticed and underserved. And we simply can’t afford the generational ignorance that is on the rise about our national and global history. Too often we teach atrocities and watershed moments (The Holocaust, Slavery, The Civil Rights Movement, Japanese Internment) as though they are a chapter that has been closed, that has ended with our syllabi.

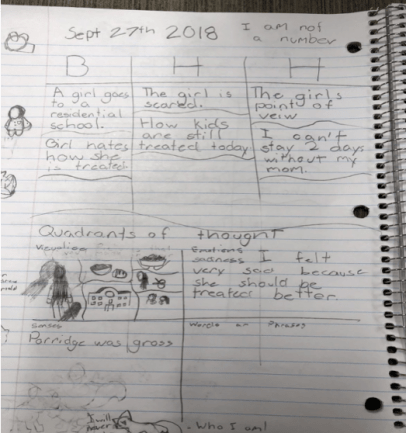

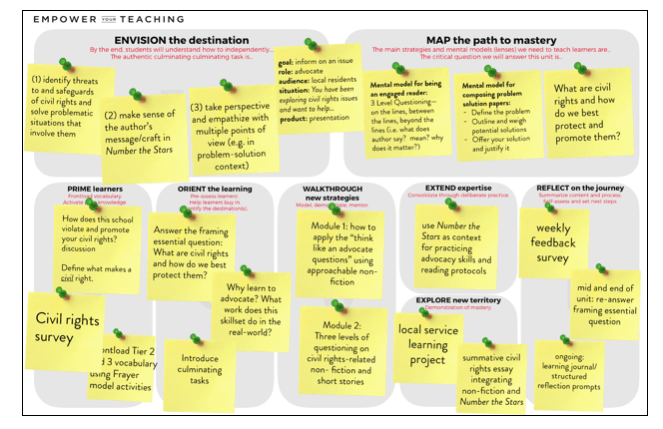

When our students come into class with current headlines, we can support their thinking by listening, supporting their questions, and turning to the intersections of history and identity: Where have we seen this before? Where do I see myself in this story? What are the gaps in my understanding? Where are connections to the present? What does the arc of history teach us about where we are today? Who holds power? Whose voices are missing? Who are the upstanders of history that stood up in the face of oppression and questioned power? Who was complicit? How do the voices of the past inform us and teach us to make meaning of the stories we create today?

Educators are tasked with the enormous feat of helping students make sense of a complex world. We go in and do our very best for them every single day. Because kids already bring an incredible sense of empathy and justice to this world, we need to join them in putting in the work ourselves. Because as I shared earlier this summer with #NerdCampMI and again at #ILA18 in a podcast later recorded by Heinemann Publishing:

Let’s transition from only posting our shock and disbelief in the state of the world to taking action to understand how we got here.

It’s time to face our history, America.

A few readings & podcasts that have helped shape my personal historical inquiries and teaching:

A Young People’s History of the United States, Howard Zinn

Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption (Adapted for Young Adults), Bryan Stevenson

Library Talks, The New York Public Library

The work of investigative reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones

Sara K. Ahmed is currently a literacy coach at NIST International School in Bangkok, Thailand. She has taught in urban, suburban, public, independent, and international schools, where her classrooms were designed to help students consider their own identities and see the humanity in others. Sara is the author of Being the Change: Lessons and Strategies to Teach Social Comprehension and coauthor with Harvey “Smokey” Daniels of Upstanders: How to Engage Middle School Hearts and Minds with Inquiry. She has served on the teacher leadership team for Facing History and Ourselves, an international organization devoted to developing critical thinking and empathy for others. You can find her on Twitter @SaraKAhmed.