By Brent Gilson

My early teaching years were in the elementary setting, where I discovered Project-Based Learning (PBL). I loved developing projects and other immersive opportunities for my students to learn and experience choice. Each year, as I moved into new grades, I could provide these opportunities until I found myself teaching Senior High English, and the pressures of standardized year-end exams started weighing down on all of us.

My first few months teaching the seniors were… boring. I was used to choice writing and exploring interests with my students, and I was stuck teaching them form and expectations based on rubrics for a test they would never use again but had a disproportionate impact on their grades. I wanted to find a balance, a way that student could explore their interests and learn the forms of writing required of them. My answer first started to form with a little (or a lot) of inspiration from the incredible Paul W. Hankins.

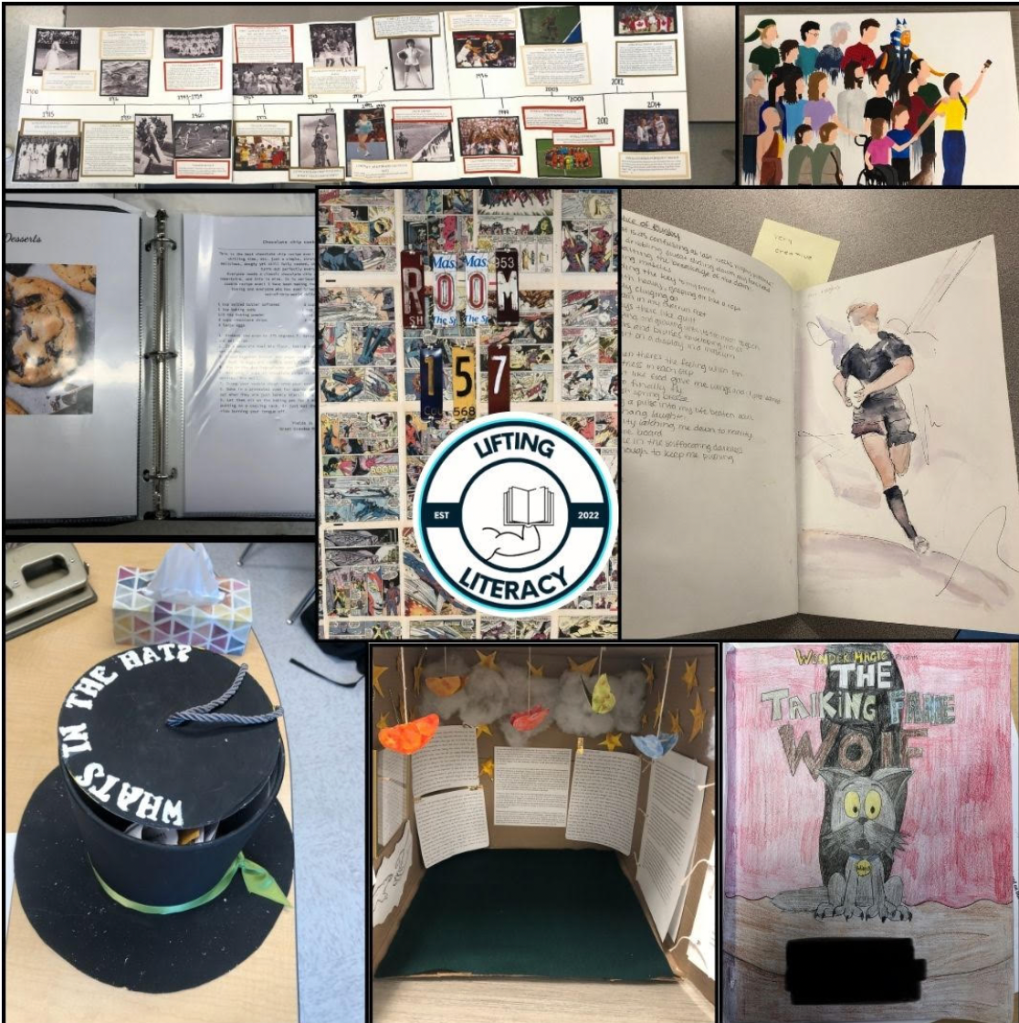

Paul and his students in the legendary room 407 brought the idea of multigenre projects and multimodal representation to life. They explored various types of writing and built incredible pieces around a theme, something my students needed to learn, and I had only been teaching most artificially. What Paul and his excellent students were creating felt so organic. After seeing some ex amples and getting some text suggestions from Paul, I dove right in. My first multigenre project was titled “Make Your Mark” a multigenre project exploring the theme of legacy.

In my first semester with the project, we had the unfortunate circumstance of COVID-19, which interrupted our time in the classroom. However, it did buy us a free pass from the tests, which were canceled. So, the project became our final. Students embraced the work at the end of the term. I had beautiful tributes written to loved ones and poems that explored the past and were hopeful for the future. Students crafted and recorded songs, built sculptures, and made movies. The creativity was off the charts. The next semester, the exams returned. I followed the same schedule, closing the year with our project, and assumed the students would be ready for their exams because of the volume of writing we were doing. That assumption was incorrect. Projects turned out amazing again, but the heavy focus on choice and joy did not translate as well as hoped to the stale exam format. I needed to make some changes.

I decided to adopt the idea of a term project in the literal sense. We would take time throughout the whole term to complete it. Introducing the project in the early days of the course, building a schedule with checkpoints, setting days throughout the course that would focus on the project, and ultimately having the project due at the end of the term. I asked the students how they felt about this process and if they felt it left them enough time to feel comfortable with their test materials while also being able to give sufficient attention to the project. The general feeling was yes, and the current form of Make Your Mark was born.

This year, I had a new class added to my schedule. The Grade 11 kids, or what I think my American friends would call Juniors? I wanted to incorporate a term project with these students as well, and this time, the answer came in the idea of Project Based Writing from Liz Prather. We started the year talking about the freedom to explore topics that interested them—things they would want to write about. We set up Fridays as our term project day. Something that will be protected so that students can better manage their time. Their first task was to develop a pitch; I explained this as a moment to share their topic, why they had chosen it, and what they envision as a final product so far. This past Friday, students shared ideas, some of the ideas included:

- Basketball Coaching Handbook and Instructional Videos

- A picture book about the life of a favorite singer

- True crime podcast series

- Field Guide on Animals of North America

- Illustrated Review of MLB ballparks

- A Food Network-type show

- A Horror Movie

This is just a sample of the creativity. Each project will require written elements such as scripts or episode summaries. Some students will submit chapters of a book after researching different authors’ writing processes. Student inspiration varied from simple interest to spite (this one made us all laugh).

As we work through the term, we have days where students will share progress and get feedback from me and their peers. We will keep a close eye on how the project is going, culminating in a gallery walk where students will have their work available for peers to experience.

I have loved the energy that term projects bring into the classroom. They are a moment to breathe in a world of testing. Students get to write about what matters to them, share their hopes and dreams, or even just their creativity. Through choice students learn to share their voice and write with one. It might not be the perfect tool to prepare for exams, but we have time for that; it just can’t be all that English Language Arts is about. Writing is about telling our stories and sharing who we are. That is often lost when we only think of ourselves as numbers.

Brent Gilson is an English Teacher in Alberta, Canada. He is in his 14th year of teaching, having spent time in grades 3-12. When not teaching, planning, or marking, Brent can be found attending student sporting events with his wife, Julie, an Elementary Principal. Brent has had the opportunity to present at various conferences in Canada and the United States, namely NCTE and ELAC (Alberta’s NCTE equivalent). If you are looking for more of his work and thoughts, check out LiftingLiteracy.com