By Katie Kelly, 2026 CCIRA Featured Speaker

With the increased attention on phonics instruction, we cannot overlook the essential purpose of reading as construction of meaning. Comprehension and critical thinking skills must be prioritized alongside foundational skills such as phonics, while also honoring and centering students’ cultural and linguistic backgrounds (Compton-Lilly et al., 2023; Duke et al., 2021). Expanding beyond narrow ideas of reading instruction to include more robust and comprehensive approaches increases students’ comprehension, engagement, and joy when reading.

Purposeful Read-Alouds

Purposeful daily teacher read-alouds serve as an easy and effective approach to supporting key aspects of reading development and engagement. Read-alouds enhance language comprehension by building students’ background knowledge, academic vocabulary, and understanding of sentence structure—key aspects that contribute to overall reading comprehension. In addition, read-alouds provide opportunities for adults to model bridging processes such as fluent reading, self-regulation, and strategic thinking (Duke & Cartwright, 2021). By modeling their own think aloud processes before, during, and after reading, adults can demonstrate how proficient readers monitor comprehension, ask questions, and make meaning from text. Thus, read-alouds not only strengthen essential language comprehension skills but also promote the cognitive and metacognitive habits necessary for independent, joyful reading.

Intentionally Selecting Read-Alouds

When selecting texts for read alouds, choose books that serve as mirrors, reflecting students’ identities, interests, and cultures allowing children to see themselves reflected, affirming their identities, making them feel valued, and increasing their interest in reading. It’s also important to select books offering windows into different stories, experiences, and perspectives to expand children’s worldviews (Bishop, 1990). When read-alouds intentionally represent a range of experiences and perspectives, children develop cultural awareness, a sense of belonging, empathy, and a deeper sense of shared humanity.

Consider:

- How does the book reflect students’ identities, cultures, and interests?

- Does it challenge stereotypes and move beyond single stories?

- Is the text authentic and accurate?

- Could the text cause harm? If so, for whom?

Secondly, it’s important to consider instructional entry points for read-alouds. Choose texts with rich language, complex themes, and opportunities for critical thinking and discussion. Explore standard alignment and students’ academic and social-emotional needs.

Consider:

- What do I want students to think about, question, or take away?

- How will this text connect with standards and help build background knowledge and vocabulary?

- What potential challenges may impede students’ understanding?

- Where can I pause to model comprehension strategies (e.g. connections, summary, inferences, asking questions, etc.)?

- What other texts can be layered to deepen understanding?

Plan ahead for unfamiliar vocabulary, abstract concepts, or cultural references. Identify moments in the text to pause and clarify ideas, build background knowledge, and invite discussion. These instructional entry points create opportunities to deepen students’ comprehension, engage in discussion, and nurture classroom community.

Book List Resources:

Read-Aloud Using the Multiple Read Framework

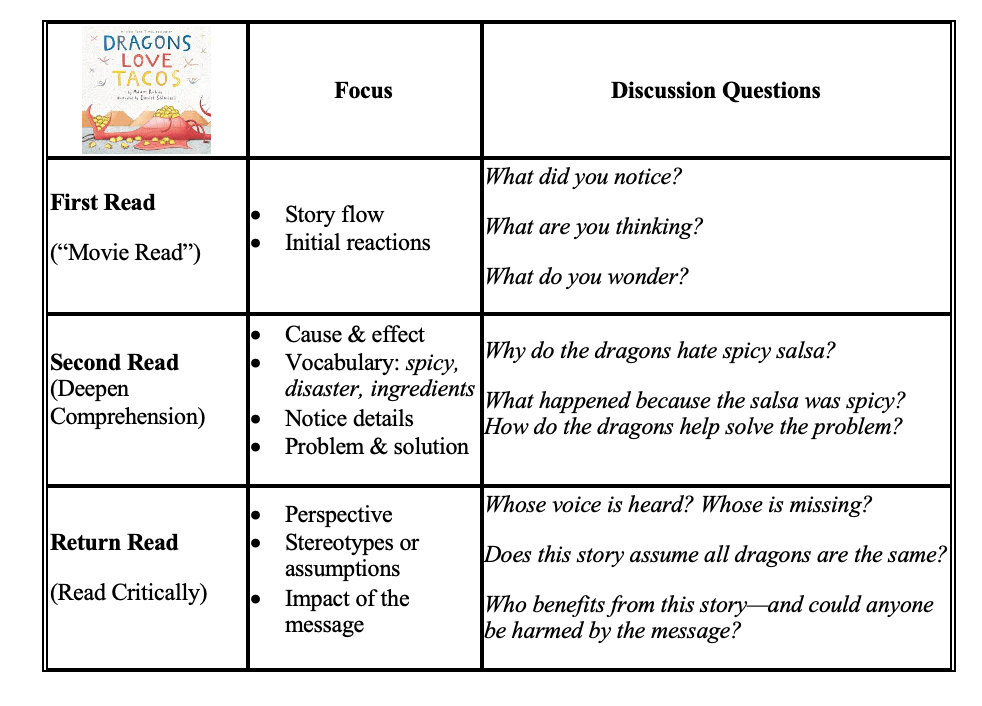

To support deeper, critical comprehension during read-alouds, engage students in multiple readings of the same text. The first read introduces the text, the second builds shared understanding, and the return read promotes critical comprehension (Kelly et al., 2023).

First Read – The “Movie Read”

Read the book in its entirety without interruption, allowing students to enjoy the story and react emotionally. Ask open-ended questions like “What did you notice?” or “What surprised you?” to build familiarity and set the foundation for deeper engagement.

Second Read – Deepen Comprehension

Revisit the text to explore vocabulary, concepts, character motivations, plot development, and key ideas to build comprehension. Model proficient reader strategies through think alouds (e.g. connect, infer, ask questions, etc.).

Return Read – Read Critically

Analyze the text to examine perspective, power, and bias. Encourage students to question the text, challenge stereotypes, and consider alternate viewpoints.

Sample critical questions include:

- Whose voice is heard? Whose is missing?

- What assumptions does this story make?

- How might a different character tell this story?

- Who benefits from the message of this text—and who might be harmed?

Tip: If pressed for time to reread the entire book for the second and return reads, revisit intentionally selected excerpts of the text based on instructional goals.

Sample Multiple Read Framework: Dragons Love Tacos by Rubin

This story helps readers understand how paying attention to details matters—even small ones like what kind of salsa is served. It also shows how trying to do something kind (like throwing a party) can have unexpected results when you’re not careful.

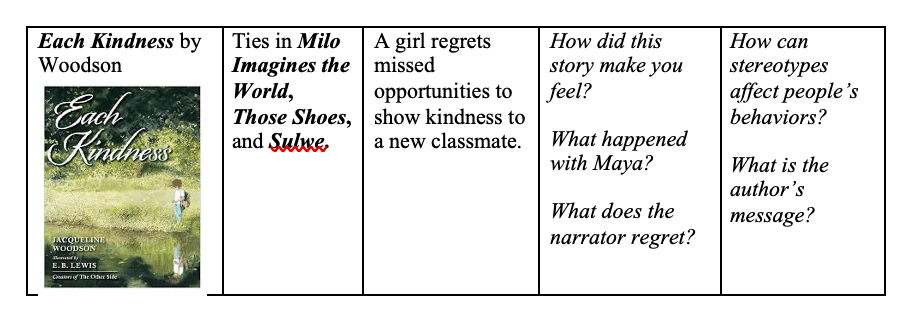

Next compare with the dragon in the The Paper Bag Princess by Munsch, then explore lessons comparing the main character, Elizabeth with female characters in traditional fairy tales. The following text set demonstrates how to build on ideas and perspectives introduced in each subsequent book.

Text Set Connections & Extensions:

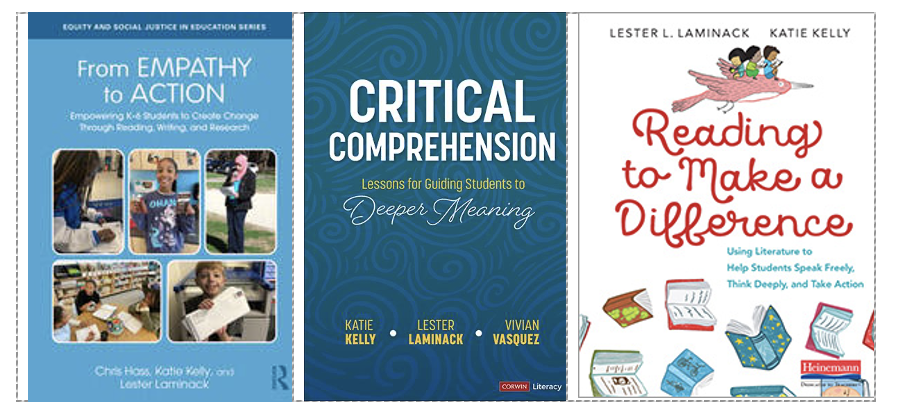

For more sample lessons using the multiple read framework, see Critical Comprehension: Lessons for Guiding Students to Deeper Meaning.

Read-Aloud as Transformation

In today’s classrooms—especially amid rising book bans and cultural erasure—it is essential to use read-alouds to center students’ voices, celebrate diverse stories, and encourage critical comprehension. Through intentional planning and repeated engagement with thoughtfully selected read-alouds, students develop not only as better readers but more empathetic, informed, and justice-oriented citizens.

Reflect:

- How will you bring more purpose to your read-alouds?

For more, check out Katie’s co-authored books including her newest book From Empathy to Action: Empowering K–6 Students to Create Change Through Reading, Writing, and Research. She can be contacted at ktkelly24@gmail.com.

References

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3), ix–xi.

Compton-Lilly, C., Spence, L. K., Thomas, P. L., & Decker, S. L. (2023). Stories grounded in decades of research: What we truly know about the teaching of reading. The Reading Teacher, 77(3), 392–400.

Duke, N., Ward, A.E., Pearson, P.D. (2021). The Science of Reading Comprehension Instruction. The Reading Teacher, 74(6), 663-672.

Duke, N. K., & Cartwright, K. B. (2021). The science of reading progresses: Communicating advances beyond the simple view of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(1), 25–44.

Hass, C., Kelly, K., & Laminack, L. (2026). From Empathy to Action: Empowering K–6 Students to Create Change Through Reading, Writing, and Research. Routledge.

Kelly, K., Laminack, L., & Vasquez, V. (2023). Critical Comprehension: Lessons for Guiding Students to Deeper Meaning. Corwin.

Laminack, L. & Kelly, K. (2019). Reading to Make a Difference: Using Literature to Help Children Think Deeply, Speak Freely, and Take Action. Heinemann.