By Lynne R. Dorfman

Every parent understands that reading is a critical skill for their children. Once they have the skill, they need to practice and learn to enjoy reading. There are many ways children can practice reading, including reading aloud, reading at bedtime, and partner reading with a sibling or friend. To continue to improve our fluency and comprehension and grow our vocabulary, we need to read year-round! Summer is just around the corner and it’s important to start to think about how we can keep our kids reading over those summer months. Summer reading is for everyone! It is essential if our students are going to retain knowledge and skills learned in this school year. Students who don’t read are at a real risk of falling behind their classmates. Teachers, along with parents and other family members, can avoid this by making sure kids set aside some time to read every day.

How to Prepare for Summer Reading

As we examine the research about readers, one thing we find that if we want our readers to go home and read over the summer, we should give our students periods of time when they can read daily while they are in school. While young people may not get better at reading just by reading alone, they certainly improve when we add the sustained silent reading time to our reading program in addition to all the other good things we are doing. In fact, children who participate in sustained independent reading programs in school show clear increases in the amount of free reading they do outside of school (Pilgreen & Krashen, 1993), and those effects seem to last years after the program ends (Greaney & Clarke, 1975).

Free choice is a factor in reading motivation (Guthrie & Davis, 2003). If we want our students to read over the summer months, then we have to be more flexible in the choices we provide our students. Do we want everyone to be a reader or are we more concerned that they read what we tell them to read? Studies of summer reading in Massachusetts (Gordon & Lu, 2008) show that low-achieving students don’t think they have free choice, while high-achieving students think that they do. Perhaps this is true because low-achieving readers typically do not do much reading outside of school – in the summer or any other time – so most of their reading is mandated by the curriculum. In order to make sure students have free choice, we have to provide alternatives to novels and the classics such as magazines, graphic novels, newspapers, and even websites (Gordon & Lu, 2008). Most summer reading programs present graded lists that narrow the choice to recommended books. If schools encourage students to read what they actually enjoy reading, they will motivate them to read more.

Access to Books

It is true that people read when they have access to reading materials and that those students who have more access to books read more (Krashen, 2004). The Columbian government dramatically increased access to reading materials. Fundalectura, a government agency, promoted a program called I Libri al Viento (Books to the Wind) and flooded the country with inexpensive reprints of out-of-copyright novels, short stories, and poetry. Books were placed at bus stops, train stations, and markets, and as a result, more people read and the literacy rates improved.

An informal student survey can help teachers know what books are in the home and what are the family members’ reading habits. Information about access to books in the home can be gathered during parent-teacher conferences. Easy access to books is important to summer reading. One way to promote summer reading is to spend some time collecting books at garage and yard sales and saving them for students to choose several books or more as an end-of-the-school-year gift. Schools or grade levels can hold book swaps during the summer months either in the school library, gym, or cafeteria if this exchange is established with principal/district approval and a committee of teachers and parents become the volunteers to run the book swap. Flyers can be sent home and posted in local markets, or on the school’s website or Facebook page.

Make it possible for the local librarian to visit your school for an assembly program – either in person or virtually. Local libraries often host summer programs that kids can join for free. Librarians can highlight new books at every level and help students make good choices.

Local reading chapters can get involved, too. If it’s possible, ask the local librarian to co-host a “Night at the Library” with you during an evening in spring for your children and their parents. You might be surprised to learn that not everyone has a library card. That night would be a good time for families to acquire one!

My chapter of Keystone State Literacy Association has hosted a book fair with a local B & N in Wyomissing. We were able to get local authors to come to read to the children and sign their books. It was so successful that we are hosting two more book fairs including one at a new location in the 2022 – 2023 school year. A Book fair in late spring with one or several children’s authors and members of the local reading council book talking the books on their award lists could stir a lot of interest. We even had a visit with a therapy dog that goes into schools to “read” with kids. One of our guest authors, Lisa Papp, read from her book Madeline and the Therapy Dog. Parents and their children were delighted!

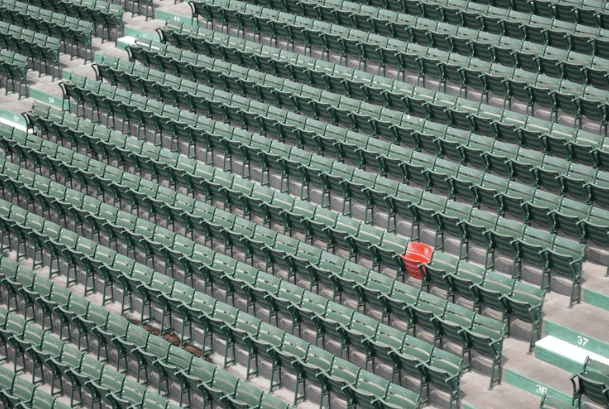

Educational Opportunities are Not Equal

The summer effect on student achievement is well researched. It is important for school districts to design inclusive summer reading programs for all students (Gordon & Lu, 2008). Research findings have consistently reported that student learning declines or remains the same during summer months and the magnitude of the difference is based on socioeconomic status (Malach & Rutter, 2003). Disadvantaged children showed the greatest losses, with a loss of three months of grade-level equivalency during the summer months each year, compared with an average of one month loss by middle-income children when reading and math performances are combined (Alexander & Entwisle, 1996). When school is not in session during the summer, there are inequalities in educational opportunities. While summer reading is a good idea, it often violates research-based beliefs about free choice, the importance of access, and the social aspects of reading. Despite what research says, summer reading lists often insist that reading be curricular and consist of “good” books. There is no attention paid to reading across nonprint media formats. Research shows that stimulating tasks increase situational interest and can increase reading motivation and comprehension (Guthrie, et al, 2006), but summer reading tasks are often limited to a book report. For most reluctant and struggling readers, writing a report about what they have read is punitive, not rewarding.

How Can We Motivate Today’s Students to Continue to Read?

Finally, summer reading and other reading motivation initiatives often have problems when they offer extrinsic rewards for reading. These rewards, combined with competition, suggest that students are resistant to reading. If we broaden our view of what students can read, that is largely untrue. Our students are reading. They are reading text messages, e-mails, and blogs. They are on twitter and Facebook. They thrive on social interaction. We need to meet our readers where they are, opening the door to reading for our tweeners and teeners by giving them choice, and access to books and computers. We should provide social interaction through reading clubs, literature circles, blogs, podcasts, and radio shows. Some social aspects of reading could be continued through summer months. Students can review books and report them in podcasts and Voice Thread. Examining current reading practices and research-based beliefs that may or may not guide our current practices can help us improve future practices. Let’s help our students be successful readers of new forms of literacy and create reading communities that translates reading into a social activity in an interactive digital environment. Let’s meet our students where they are! Summer is coming. What will you do to help your students continue to read over the summer months?

Lynne Dorfman is an adjunct professor at Arcadia University. She enjoys her work as a co-editor of PA Reads: Journal of Keystone State Literacy Association and past co-president of KSLA Brandywine/Valley Forge, She is also a past president of Eta, a chapter of Alpha Delta Kappa. Dr. Dorfman is a co-author of many books including Grammar Matters: Lessons, Tips, and Conversations Using Mentor Texts, K-6 and A Closer Look: Learning More About Our Students with Formative Assessment, K-6. Her newest book, Welcome to Writing Workshop, is with Stacey Shubitz.