By Carl Anderson

Imagination is more important than knowledge.

–Albert Einstein (1929)

Creativity is as important as literacy and we should afford it the same status.

–Ken Robinson (2006)

In my new book, Teaching Fantasy Writing: Lessons that Inspire Student Engagement and Creativity K-6, I explore why it makes sense to include a study of fantasy writing in elementary and middle school writing curriculums. Children are permitted to write “real or imagined stories” (emphasis added) to meet narrative standards in many U.S. states. Since writing fantasy is extraordinarily engaging, it accelerates children’s learning about writing, and, almost like magic, helps them acquire powerful writing skills. And fantasy also is a genre that offers children a unique creative space in which to write about issues of great personal significance, such as making friends, dealing with bullies, gaining confidence and fighting injustice. In this, they follow in the footsteps of beloved and influential fantasy writers, such as J.R. Tolkien and Robert Jordan, whose stories reflected their respective experiences during World War I and the Vietnam War, and J.K. Rowling, whose writing helped her to work through grief and depression (Livingston, 2022; Pugh 2020).

Fantasy also gives teachers the opportunity to help students develop their creative skills. This is important because children in grades K-12 are experiencing a decades-long “creativity crisis” (Bronson and Merryman, 2010). Educational scholar and creativity researcher Kyung Hee Kim (2016) points out that scores on the most reliable measure of children’s creativity—the Torrance Test—indicate that 85 percent of children today are less creative than children in the 1980’s.

What accounts for this creativity crisis? One significant reason is that, since the 1990’s, school curriculums have become increasingly more standardized, a change driven to a large degree by the pressures of testing. As curriculums has become more standardized, play-centered activities have been squeezed out of the school day. This is a problem because play is “one of the driving engines of child development” and “encourages flexible, imaginative out-of-the-box thinking” (Straus, 2019).

That students are less creative has profound implications for their lives, and the world. More and more, the successful futures we want for children depend on their moving into adulthood with imaginative and creative skills. In his books, The Global Achievement Gap (2008), and Creating Innovators: The Making of Young People Who Will Change the World (2012), Tony Wagner names and describes seven 21st Century “survival skills” that students need to succeed in today’s innovation economy and to be social disruptors who can tackle today’s problems. One of these skills is “curiosity and imagination,” which Wagner says students develop when their childhoods are filled with creative play.

How should schools respond to the creativity crisis? They need to engage children in play-centered activities that exercise their creativity and imagination—such as writing fantasy stories in an ELA class.

What? Children writing about the adventures of wizards and unicorns can be part of the answer to the creativity crisis? Yes! When children write fantasy, students create what psychologists call paracosms, or detailed imaginary worlds. The term used when someone creates a paracosm is worldplay (emphasis added).

Yes, play can be academic. Writing can be play.

If you’ve read Bridge to Terabithia by Katherine Patterson, you may remember that one of the main characters, Leslie Burke, creates the imaginary kingdom of Terebithia. She and her friend, Jesse Aarons, enter Terabithia by swinging on a rope across a creek behind Leslie’s house. Once there, they pretend they’re the king and queen of the kingdom. The world of Terabithia is Leslie’s paracosm, which she shares with Jesse.

Psychologists have discovered that nearly one in five children create paracosms on their own, usually in middle childhood (Taylor et al., 2018). Research has shown links between this childhood worldplay and adult artistic success, as well as creative success in the sciences and social sciences. Many notable people created paracosms as children, including Amadeus Mozart, Charlotte and Emily Bronte, and Friedric Nietzsche and C.S. Lewis, among others. A study of one group of highly creative people, the MacArthur fellows, all winners of the award colloquially known as the “genius grant,” showed that 25 percent of them had paracosms as children, and that their worldplay often continued into adulthood as part of their creative process (Gopnik, 2018; Root-Bernstein, 2009).

When fantasy is included in a writing curriculum, every child in the classroom, with their teacher’s guidance, gets to engage in worldplay and create paracosms.

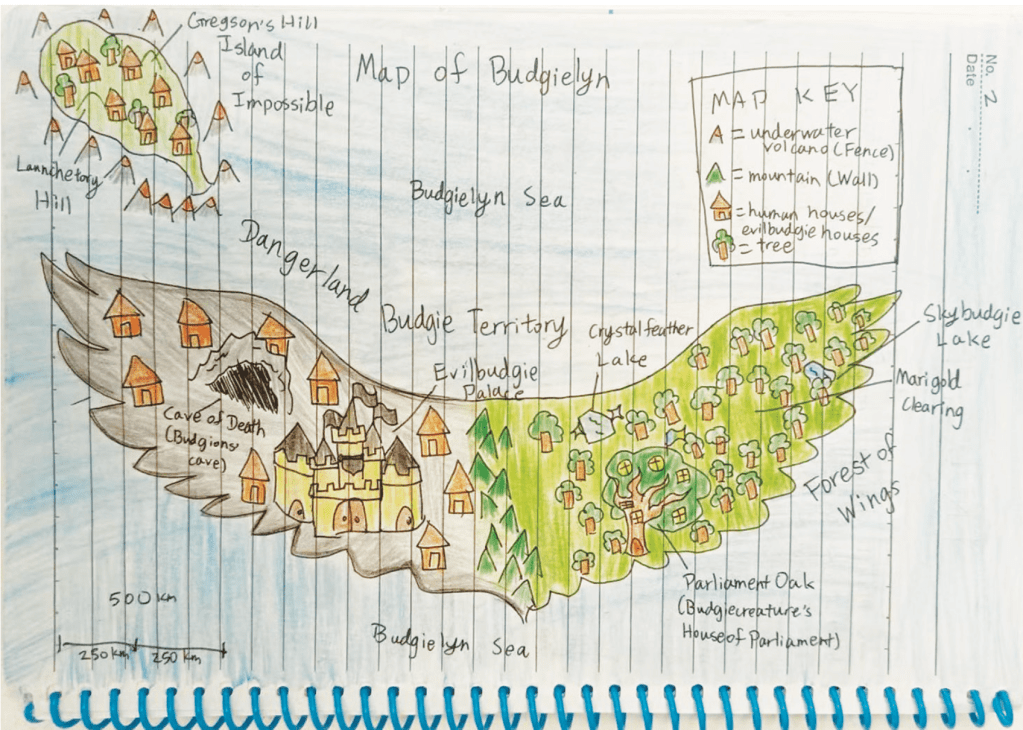

For example, as part of learning how to write fantasy, Alyssa, a fifth grader, created the intricate imaginary world of Budgielyn. Alyssa populated Budgielyn with all sorts of “budgie creatures,” such as budgie fairies and budgiecorns, as well as a variety of evil budgie creatures. (To create Budgielyn, Alyssa drew upon her deep love of her pet budgies as inspiration).

Having built her Budgielyn world, Alyssa wrote “Grace’s Journey,” a story of a brave and plucky girl who goes on a dangerous quest to fight evil and bring balance to Budgielyn. As she makes her world a better place, Grace develops new confidence in herself – and helps readers imagine they could do the same. Throughout the story, readers encounter the fantastical magical creatures and wondrous settings that sprung from Alyssa’s imagination as she created her fantasy world.

As part of the research for Teaching Fantasy Writing, I studied the ways that experienced fantasy writers created imaginary worlds, and adapted their strategies for children in primary, upper elementary and middle school grades.

In the upper grades, we can teach students a multi-step process for creating fantasy worlds. Students will enjoy—even love—this aspect of fantasy writing, since it invites them to use their imagination in exciting, creative ways. The best way for teachers to teach these steps is for them to first go through the steps themselves, and then show their work to students as a model:

- First, have students sketch a physical world — which can be an island, a coastal area, a large landform, or (if the student wants to write science fiction) a planet, including geographical features such as forests, mountains, lakes, rivers, deserts, etc.

- Next, have students populate the world with beings and creatures, as well as the towns, castles, caves, and forts where they live. The sky is the limit here—students can choose humans, witches and wizards, elves, unicorns, fairies, dragons, aliens – any kind of fantasy characters!

- Then have students do some writing about the “magic system” of the world. What magical powers will the beings and creatures in the world have? Which latent powers can they develop, and under what conditions?

- It’s also important for students to do some writing about how the different groups of beings and creatures in their fantasy worlds get along. Is one group in power, or trying to gain power? Which groups are in conflict? Which groups are allied with each other, or work together?

- Finally, have students create a main character from one of the groups of beings and creatures. This character will be the protagonist of the story they will tell. Also have students create a secondary character. As the main character meets the central challenge of the story, the secondary character will function as their ally or obstacle, their sidekick or their nemesis.

After students have completed their worldplay – a process they will love, and one that will boost their writing skills and their imaginations — it’s time for them to write stories set in their fantasy worlds. As they write, teachers show them mentor texts to teach them about the craft techniques experienced fantasy writers use, techniques students then try out in their own stories.

In the primary grades, I’ve learned that young children, rather than engage in worldplay as a separate step prior to writing their fantasy stories, do both at the same time. Since their composing process usually includes a combination of drawing illustrations and writing text, they create their imaginary worlds as they draw their illustrations. To help them with this process, we can teach them to ask these questions before they start writing a story:

- First, what kind of fantasy story do you want to write? A fairy tale? A science fiction story? A magical adventure story (like Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are)?

- What kind of setting is usually in the kind of story you want to write (a castle in a fairy tale, outer space in a science fiction story, etc.)?

- What kind of beings and creatures are usually in this kind of story (a royal family and their attendants, and dragons in fairy tales; humans and magical creatures in a magical adventure story; etc.)

How will children have the knowledge of fantasy stories necessary to navigate the steps of worldbuilding? While some already have an extensive knowledge of fantasy, developed through read-alouds at home, their own independent reading, and/or by watching TV shows and movies, some aren’t as familiar with fantasy. As teachers, we can help all students learn about the genres of fantasy and their characteristics by immersing them in a variety of subgenres – such as fairy tales and science fiction – at the beginning of the unit. (In the book, I provide recommended lists of fantasy mentor texts for fantasy units for grades K-1, 2-3 and 4-6.)

Over the past several years, in fantasy writing residencies in K-8 classrooms all over the United States, I’ve taught lessons on how to create imaginary worlds and craft fantasy stories, both in whole and small-group lessons, and in 1:1 writing conferences. The students I’ve had the privilege of teaching have shown higher levels of excitement and engagement than I have seen in many years. These young writers have flabbergasted me and their teachers with their creativity and narrative writing skill.

So, how do we solve the creativity crisis plaguing our children, and diminishing their prospects for the future? Including fantasy in our writing curriculums is one of the answers!

WORKS CITED

Bronson, Po and Ashley Merryman. “The Creativity Crisis.” Newsweek, July 10, 2010.

Einstein, Albert. 1929. Quoted in, “What Life Means to Einstein: An Interview by George Sylvester Viereck.” The Saturday Evening Post, October 26, 1929, p. 117.

Gopnik, Alison. “Imaginary Worlds of Childhood.” The Wall Street Journal. September 20, 2018.

Kim, Kyung Hee. 2016. The Creativity Challenge: How We Can Recapture American Innovation. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books.

Livingston, Michael. 2022. Origins of the Wheel of Time: The Legends and Mythologies that Inspired Robert Jordan. New York: Tor.

Patterson, Katherine. 1977. Bridge to Terebithia. New York: HarperCollins.

Pugh, Tison. 2020. Harry Potter and Beyond. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

Robinson, K. (2006). Do schools kill creativity? [Video]. TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/sir_ ken_robinson_do_schools_kill_creativity?language=en

Root-Bernstein, Michele. 2009. “Imaginary Worldplay as an Indicator of Creative Giftedness.” Chapter 29 in International Handbook on Giftedness, edited by L.V. Shavinina. New York: Springer.

Sendak, Maurice. 1963. Where the Wild Things Are. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Straus, Valerie. 2019. “Should we worry that American children are becoming less creative?” The Washington Post, December 9, 2019.

Taylor, Marjorie, and Candice M. Mottweiler, Naomi R. Aguiar, Emilee R. Naylor, and Jacob G. Levernier. 2018. “Paracosms: The Imaginary Worlds of Middle Childhood.” Child Development, Volume 91, Issue 1, pp. e164 – e178.

Wagner, Tony. 2012. Creating Innovators: The Making of Young People Who Will Change the World. New York: Scribner.

_____. 2008. The Global Achievement Gap. New York: Basic Books.

Carl Anderson is an internationally recognized expert in writing instruction for grades K-8, and consults for schools and districts around the world. A regular presenter at national and international conferences, Carl is the author of many professional books for educators, including Teaching Fantasy Writing: Lessons that Inspire Student Engagement and Creativity and How to Become a Better Writing Teacher (with Matt Glover). Carl began his career in education as an elementary and middle school teacher. And since Carl was a boy, he has loved visiting fantasy worlds in epic fantasy novels and movies.